The mysterious Ogham

Ogh what? I hear you say. Imagine striding across moody moors covered in shades of gorse and bracken. A weathered standing stone looms out of the shifting mist, strange markings cover the edges. What is it? Who put it there? What is it saying?

By Gurnam Bubber

Rooted firmly to the earth it looks like a part of the landscape, a gateway to the ancients and our imagination. You may have just stumbled across a stone monument with the mysterious script known as ogham.

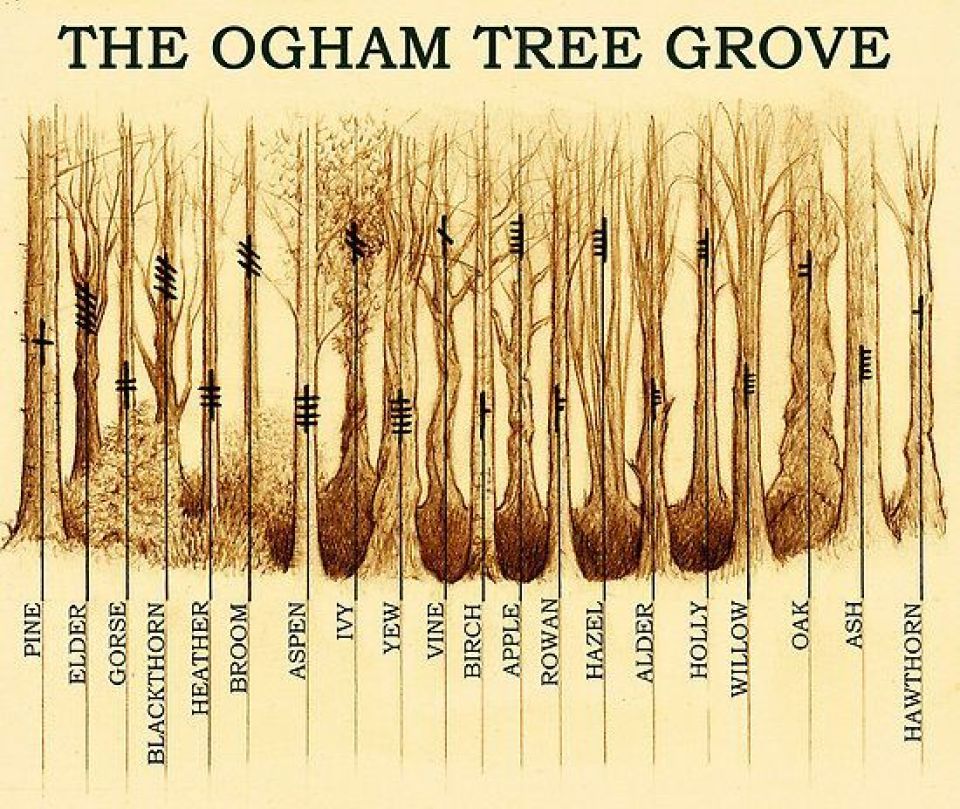

Ogham is an alphabet that appears on monumental inscriptions dating from the 4th to the 6th century AD, and in manuscripts dating from the 6th to the 9th century. It was used mainly to write Primitive and Old Irish, and also to write Old Welsh, Pictish and Latin. It was based on a high medieval Briatharogam tradition of assigning the name of trees to individual characters.

Yes indeed, trees have been such an integral part of the human psyche that a whole alphabet was inspired by them, the ogham, also known as the Gaelic or Celtic tree alphabet.

It’s thought that this association with trees played a role in Gaelic language education. Like runes, each ogham symbol has a name: the letter ‘b’ is called beithe, ‘birch’ and the letter ‘c’ is coll, ‘hazel’. Bardic students learnt these basic names and used the ogham sequences to create lists for memorisation.

In a 2017 interview with Emily McEwan of Gaelic.co, linguist and polyglot Dr. Conor Quinn explained how the ancient Irish script works: "Ogham, quite delightfully, is one of the few alphabets written and read vertically from the bottom to the top.

Its twenty letters, called feda (= ‘trees’), group into four aicme (= ‘family, tribe’) of five letters each. Each letter is simply a cluster of one to five straight lines, scratched along the (usually) vertical edge of a stone.”

As far as what ogham was used for, Dr. Quinn explained: "All we know directly for certain is its use in writing personal names, in possessor form (So-and-So’s…), on the edges of standing stones and the like, as memorial (and possibly as territory/boundary) markers.But references in Old Irish (and later) literature also have characters writing ogham on sticks to send messages, to record information, and to do magic.”

There are roughly 400 surviving ogham inscriptions on stone monuments throughout Ireland, Scotland and western Britain. The largest number outside Ireland are in Pembrokeshire, Wales.

It's origins are shrouded in the mists of time and have been debated for years. Part of the difficulty is that dating ogham is often problematic. Though it is thought that the alphabet itself was created earlier, the evidence suggests that the surviving inscriptions of ogham in Ireland belong predominantly to the fifth and sixth centuries.

There are many popular theories vying with each other as to the origin of Ogham and no clear winners so far. This is no surprise as the script has similarities to ciphers as varied and different as Germanic runes, Latin, elder futhark and the Greek alphabet!

Mythical theories for the origin of ogham also appear in texts from the eleventh to fifteenth centuries. The eleventh century Lebor Gabala Erenn tells that ogham was invented soon after the fall of the tower of Babel, as does the fifteenth century Auraicept na n-eces text. The Book of Ballymote also includes ninty-two recorded secret modes of writing ogham written in 1390-91 CE. Alternatively the Ogam Tract credits Ogma (Ogmios) a Gaelic god, with the script's invention. Ogma was skilled in speech and poetry, and created the system for the learned, to the exclusion of rustics and fools.

There are some particularly interesting examples of standing stones that reveal further the complexity of human history within these islands. In Shetland, ogham has been found representing Norse words such as dattur (daughter) and krosk (cross) and, in Killaloe, Co. Clare, a particularly fascinating stone has a commemoration from c.1100 dedicated to a Scandinavian settler, Torgrim, which is written in Norse runes and then replicated in ogham.

We may never know the true origins of ogham and all its uses. What is certain is that the ancients were fascinated with the natural world which had great significance and meaning for them. Trees were a hugely important part of their everyday lives and played a key symbolic role leading to this ingenious alphabet. We catch a glimpse of their world when we see which trees were chosen for the alphabet.

We still carry a form of that same connection to nature within us today even in the modern world. It’s amazing to think that hundreds of years ago people were so inspired by the beauty of trees that it led to a whole script. If you happen to be walking in the old Celtic countryside you may come across a stone with the alphabet of trees inscribed on it, let it take your imagination for a stroll back to those ancient trees and scribes.

Fun activities for the whole family

- For a bit of fun you could use an online transliterator to see what your name would look like in ogham.

- There are online activities for kids where they can have a go at translating and writing on their very own ogham stones here and here

- For the nerds out there the Omniglot site has the whole alphabet and this one lists the natural history of the trees used in ogham.

- Another fun activity could be making ogham divination sticks or cards. This site lists the letters and their new age pagan meaning.

Love all things trees?

Get your monthly dose of tree facts, planting events, and green inspiration with the Trees for Cities newsletter.

Green up your inbox!Discover some of the other species of urban trees.

Beech is a large deciduous tree with smooth grey bark and can grow to a height of 40 metres. It develops a domed crown which spreads out into a dense canopy. Beech trees are monoecious which means they have male and female flowers on the same tree. These catkin flowers grow in April and May, male flowers are yellow, outlined in red–they hang as catkins from the branches. Female flowers are yellow and arranged in pairs. They are wind pollinated.

Alder is monoecious, which means that both male and female flowers are found on the same tree. They take the form of catkins that appear in early spring, between February and April, usually before the leaves. Male catkins are yellow and pendulous, dangling from the branches at about 2 to 6 cm long. Female catkins are green, small and rounded, and are grouped in numbers of three to eight on each stalk. After wind pollination the female catkins gradually turn into brown and woody fruit by autumn, taking the form of unmistakable tiny cones. When ready they open and disperse their seeds on the currents of wind and water. The clever seeds, or nutlets, are flat and waxy and have two corky wings containing air bubbles, which allows them to float and to be carried away by water. The cones remain on the tree during the winter, long after the seeds are gone, and if you spot them, you’ve found an alder!

The hawthorn (Crataegus Monogyna) has small lobed leaves and thorns (see pictures). Very young stems are reddish in colour, the bark is brown with occasional orange cracks, sometimes green algae are found along the bark. The leaves appear before the flowers in spring, which are small, scented, usually white and appear in abundance. The fruits emerge in autumn, they are red berries known as haws and are a very valuable source of winter food for birds like thrushes and waxwings.

Donate to Trees for Cities and together we can help cities grow into greener, cleaner and healthier places for people to live and work worldwide.

Donate