The weird and wonderful world of the Plant Hunters - part 2

Part 2 – the Squashbuckling gathers pace!

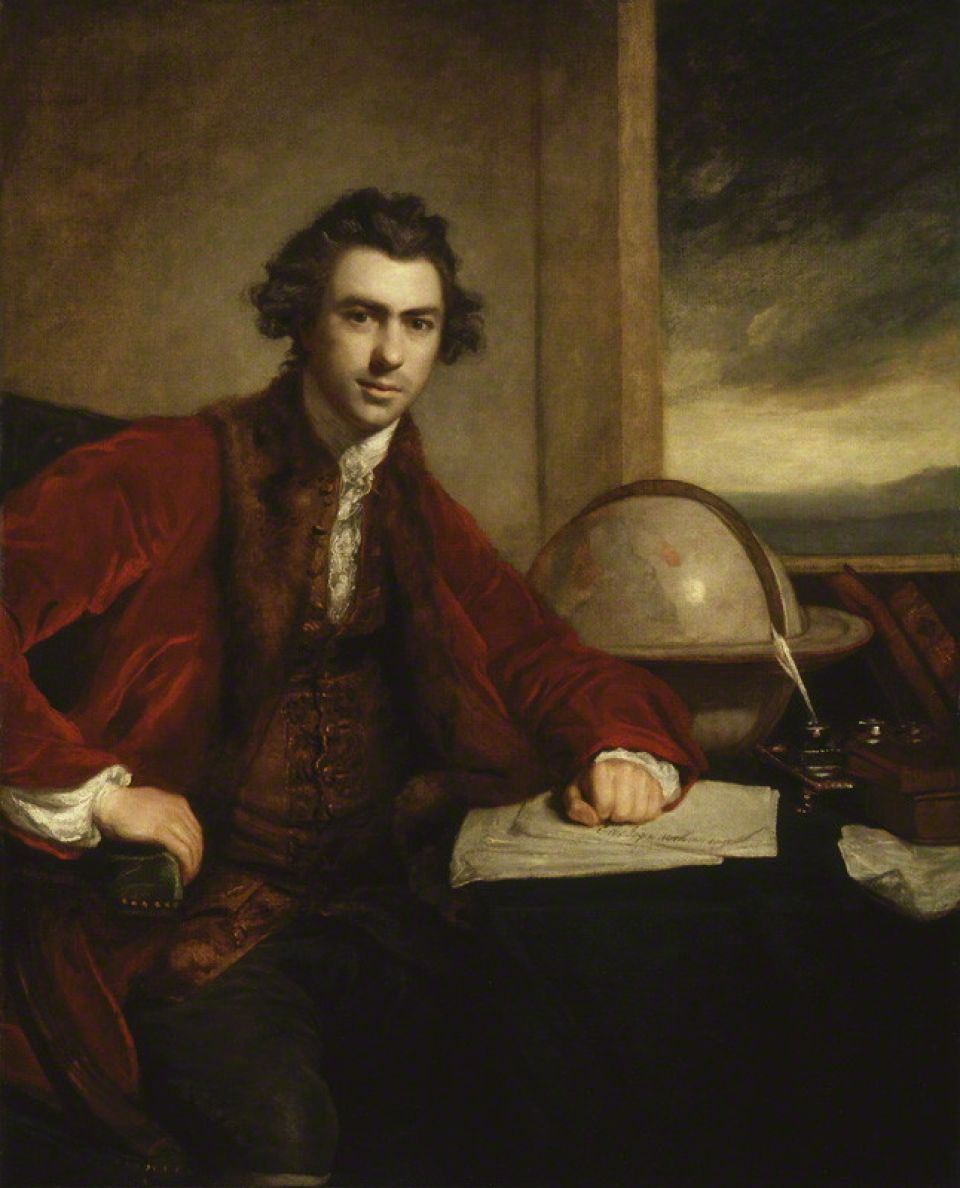

Joseph Banks

Moving forward to the 18th Century, Sir Joseph Banks was an outstanding scholar and became probably the most influential scientist of his time. He had a lifelong passion for botany and discovery. He came into his inheritance early and became one of the richest young men in Britain. Soon after, he was appointed adviser to George III who requested that he support voyages of discovery. He was able to sail with Captain Cook on the Endeavour to South America, New Zealand and Australia.

In Brazil he discovered Bougainvillia, and in the South Seas he curated the first major plant collection. Some of the plants he is credited with introducing are New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax), Crimson bottlebrush (Callistemon citrinus) Eucalyptus, Acacia, and Mimosa.

Sir Joseph was elected president of the Royal Society, a position he held for more than 40 years. He was named Advisor to the King on the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew and supported many voyages of discovery. He served as a trustee at the British Museum for 42 years.

Ernest Wilson

One story that best expresses the heroic nature of plant hunting is the story of the Handkerchief tree. This would be the start of the career of one of the most well-known Victorian plant hunters, Ernest Wilson. He was later known as ‘Chinese’ Wilson after his very successful expeditions to China between 1899 and 1905. Much of his collecting was carried out while employed by the famous Veitch Nurseries. 'Chinese' Wilson is credited with the introduction of over 1,000 significant plant species.

Before we get to Ernest’s relationship with the tree, we must recognise the first European to discover it. He was the French Jesuit priest Father Pierre David, who came across the tree when he travelled to remote parts of China in 1868. This was at a time when few Europeans were allowed into the country, so this was quite remarkable.

The second European to witness this tree said, “It seemed as though the branches had been draped in thousands of ghostly-white handkerchiefs.” These are actually the bracts and not flowers. Though Father Pierre is credited with the “discovery” of this tree, it was of course well known to local people who had “discovered” it much earlier. The Chinese saw the white handkerchiefs as doves and so called it the dove tree. Inspired by the story of a famous Chinese heroine, a real person called Wang Zhaojun. She lived from 52 - 19 BC and was a concubine of the Han Dynasty emperor Yuan.

Specimens of this tree sent to Kew caught the attention of nurseryman, Henry Veitch, who in 1899 commissioned the young Kew trained botanist Ernest Wilson to bring seeds of the tree from China. Wilson had never been abroad before and so at the tender age of 22 began his life of adventuring with a nightmare journey, full of danger and frustration. He only had a hand-drawn map and a few written instructions to guide him into the remote Yunnan region of China in search of the single known existing specimen. On his way, he escaped local bandits, he was imprisoned on suspicion of spying, survived an epidemic of deadly fever and nearly drowned when his boat overturned in a rocky river.

After enduring all these hardships, when he finally found the location of the tree, to Wilson’s dismay he saw that it had been cut down and used to build a house! Bitterly disappointed after everything he had been through, Wilson turned to collecting other plants and stumbled across a clump of the Handkerchief trees by accident. But it was still not straightforward. They were in flower and with the threat of the anti-foreigner Boxer rebellion brewing around him, he had to wait weeks for the seeds to develop. At long last he had them and was able to send them back to England. He went on to spend many years in China and became one of the best-known plant hunters of his generation.

Marianne North

In this world of boys’ own adventurers some women bucked the trend and ventured forth themselves. The biggest and baddest of them was Marianne North, who single-handedly documented 900 plant species.

North would discover numerous plants, but unlike most male naturalists of the time, she didn’t stuff rare flowers in her suitcase to show off back home. She simply painted what she saw with a scientific accuracy that would make her paintings vital botanical records. And by replacing ‘ladylike’ water colours for oil paints and painting flora in their immediate environment rather than as individual plants against a white background, North’s style was unique.

Painting was an acceptable pastime for the Victorian upper-class woman and so started the extraordinary life of Marianne, the eldest daughter of an English member of parliament. Born in 1830 into a wealthy family she was not satisfied with the tame life of painting flowers in her garden. At the sprightly age of 40 she set off to travel the world alone and relished a rough and simple life. In only 14 years, she documented 900 plants with her immeasurable talent. This would have been impossible without her wealth, family connections and the fact that she never married. “Marriage? A terrible experiment,” she once wrote.

North’s great journey started in 1871 with a trip to Canada, the US, and Jamaica. She then moved on to Brazil where she bushwhacked through the Amazon for eight months to paint its as yet undiscovered flora. Over the next 13 years of travel her odyssey took her around the world twice over.

Marianne North knew how to live, wherever she was in the world, her days would begin at dawn when she would take her tea outside to watch the morning unfold. She would then paint frantically outdoors till noon, consumed in what to her was “a vice like dram-drinking, almost impossible to leave off once it gets possession of one.”

Rainy afternoons were spent painting indoors, while evenings were given over to exploring outdoors and returning home well after dark. Her life, as she described it, was one of “wander and wonder and paint!”

North was privileged, her family name granted her letters of introduction to ambassadors, viceroys, and rajahs all over the world; she even travelled to Australia on the personal recommendation of Charles Darwin, but by traveling mostly alone and battling her way through hostile terrain, often on rickety transport, there’s no doubt that Marianne was a true adventurer.

Begin now by observing as much as you can of what nature teaches, and you will find a new happiness in life.

Marianne North

North preferred a simple life, rather than travel with trunks full of clothes to serve her well at colonial soirees, North’s entire wardrobe could be contained in one small suitcase. In fact, the thought of having to appear at formal dinners in a corseted and constricting evening dress was a torture for her, and she wrote to her sister from Jamaica: “These unthinking croqueting-badminton young ladies always aggravated me and I could hardly be civil to them.”

In 1882, a gallery of North’s work, which she funded herself, opened at England’s Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. At a time when photos were still in black and white, North’s paintings provided the scientists at Kew and the general public an intriguing glimpse of the world beyond Europe.

With her health failing, probably as a result of the harsh conditions of her travels, North died at home in Gloucestershire in 1890. She was 59.

Over 130 years later, North’s 832 paintings are still on show in the same tightly packed formation, as when the gallery first opened. It is still the only permanent space dedicated to a single female artist’s works in Britain. The Marianne North Gallery is also one of the most important collections of botanical art in the world.

For more about this fascinating painter, watch the BBC documentary Kew’s forgotten Queen available on You Tube.

David Douglas

Another famous Victorian plant hunter and colourful character was David Douglas. His namesake is one of his best-known introductions, the magnificent Douglas fir. He was known as an explorer and adventurer as well as a plant hunter. Reputedly he wrestled with grizzly bears and lived like the indigenous people in America. All very shocking behaviour for the times!

His life and death highlight the real dangers and difficulties he and explorers of the time faced. The quotes below are from his letters.

“"An intermittent fever dreadfully fatal broke out...11 weeks ago... not a soul remains!! The houses empty and the flocks of famished dogs howling and dead bodies in every direction... I am one of the very few among the persons of the [Hudson Bay] Company who have stood it...The ship which sailed with us was totally wrecked on entering the River but I am glad to say no lives were lost. To this ship I was at first appointed and... I should have lost my all." [Archive ref: DC61 f.96]”

“"You must tell Joseph I have now a mortal antipathy (more if more can be) to cockroaches than he has for I made a great many observations at the Sandwich Islands...and the vile cockroaches ate up the whole paper and as there was a little oil on my shoes they nearly ate them up." [Archive ref: DC61 f.108]

He returned to Vancouver and in March 1833 set off up the Columbia and Thompson Rivers to Stuart Lake, in British Columbia. Unable to find a party going to the coast, he travelled back down the Fraser River and there met with disaster:

"At the 'Stony Islands' of Frasers River...my canoo [sic] was dashed to pieces when I lost every article I then possessed...the collection of plants was about 400 species, of which 250 were mosses - a few of them were new. I cannot tell you how much this has worn me down." [Archive ref: DC61 f.112]

To add to his suffering, Douglas's adventures had clearly taken their toll on his health by this time. As he wrote:

"My left eye is infinitely more delicate than ever...but my right one is no longer useful to me...I fear that the attack of ophthalmia I had in 1826 then snow-blindness then the intense scorching heat of California...has ruined it. I use purple goggles for the snow...against my reluctance for it makes all plants this colour." [Archive ref: DC61 f.110]

Douglas made it back down the Columbia River and in November 1833 again sailed for Hawaii. Sadly, this was to be his last adventure as just eight months later he was found dead in a pit trap, trampled by an enraged bull. The circumstances surrounding his death sparked rumours of murder, but a subsequent investigation found no evidence of this.”

Douglas had a touching relationship with his little terrier Billy who came with him on all these perilous journeys. In a fantastically detailed letter from the Columbia River, dated 9 Apr 1833, Douglas lists all his personal effects as he sets out to cross Mackenzie's track at Fraser River. Alongside fifty pounds of biscuit, 12 pairs of moccasins, and a pair of deer skin trousers, he takes his:

“most faithful, and now, to judge from his long grey beard, venerable friend who has guarded me throughout all my journies [sic], and whom, should I live to return I mean certainly to pension off, on four penny worth of cat's meat per day!” [Archive Ref: DC61 f.110]

Gairdner wrote to Kew's then Director Sir William Jackson Hooker that Douglas' body:

“was only discovered on the suspicions of the islanders being excited in consequence of seeing his little dog Billy sitting alone on his coat which he had put off in order to be free of encumbrance.” [Archive Ref: DC62 f.82]

Billy actually made it all the way back to England from Hawaii! And lived out his remaining days in the care of a clerk in the British Foreign Office.

Douglas introduced more than 200 plants to this country, but it was the large conifers, including Sitka spruce and Grand Fir that had the most dramatic effect on our garden and commercial forestry landscapes. Among his collections at Westonbirt Arboretum was the Monterey pine. His gruesome death in 1834 in North America, illustrates just how dangerous plant hunting life was, he was only 35.

This is only a taste of the hazardous life of a plant hunter - their adventures were perilous to say the least! Join me for the next chapter when we’ll look at the cases that took plants, trees and shrubs from the furthest reaches of the empire to our small island and beyond.

Donate to Trees for Cities and together we can help cities grow into greener, cleaner and healthier places for people to live and work worldwide.

Donate