Time to go catkin spotting

Out in our green spaces the first signs of spring are starting to glimmer. Snowdrops and daffodils and lambs’ tails. Think it’s a bit early for lambs in a field, and you’d be correct. These are tails on a tree not a woolly lamb and you can see them even on a busy urban street. Confused? Read on to find out more.

Right from their distant evolutionary beginnings, trees had to crack the problem of how to reproduce while being rooted to one spot. Pollen is their crafty answer.

Pollen is a fine powder made up of small tough coated particles that carries one tree's genes to another. Transportation for the pollen grain can be the wind or another creature. Wind pollination is called anemophily. About 12% of the world’s flowering plants are wind-pollinated, including grasses, cereal crops and many trees. Wind pollination is a much more understated and quiet affair. It’s hush hush compared to the brash blowsy flowers and attendant creatures of the pollination process we’re more familiar with.

The carpel is made up of an ovary, a style sticking out from it, and a pollen-receiving stigma located at the tip of the style. There are variations on this theme, but this is the archetypal flower. When pollen reaches the stigma, it germinates, sending a tube through the style to fertilise the ovule. This act of pollination leads to the amazing formation of new life in the form of fruits and seeds.

Pollen appears in spring as a powdery cloud of fine, yellowish grains. Sometimes it’s even possible to see clouds of this pollen on a large scale in the landscape, though we’ll probably only notice it when it ends up coating our cars rather than the intended recipients.

Check out clouds of pollen being released

Globally, the incidence of wind pollination increases with both latitude and elevation. It is most common in our temperate deciduous and in boreal forests but pretty uncommon in tropical rain forests. The high levels of rain and humidity reduces the ability of pollen to travel in the air.

Wind pollination is most effective in drier open habitats and in early successional ecosystems, where wind is likely to be an advantage. It is common among forest trees that are high enough so that their flowers or cones are exposed to winds, but almost non-existent among understory plants, which live in less wind-prone conditions. Nearly all of our common conifers, including pines like spruces, and firs, rely on wind pollination. Many broadleaved trees do too, including aspens, hazel, oaks, ashes, elms and birches. These hardwoods all share a common type of male flower that’s elongated and hangs down (called catkins) so that the slightest breeze will release the pollen grains. It has multiple small flowers arranged in a spike.

Catkins not only sound cute but can come in a variety of forms, some of the earliest and classic catkins belong to hazel, also known as lambs’ tails (see hazel article for more on the magic of hazel). Others like the willows range from producing furry ‘pussy willow' catkins to more alien like structures. These shed pollen when the leaf buds are opening. Depending on the willow variety, flower colours vary from creamy white (the white willow, Salix alba) to a bright greeny yellow.

Many trees, such as oak, and ash, cleverly avoid interference from leaves by forming flowers and shedding their pollen well before their leaves come out. The female flowers of these trees don't usually come in the shape of catkins but develop small, round and hard-to-see flowers. Trees such as Sycamore have lovely green flowers, but from a distance they will often be mistaken for the leaves. Late winter and early spring are the times to keep an eagle eye out for these unassuming flowers.

But relying on the vagaries of wind and weather to deliver pollen is quite a bit of a gamble and trees need to improve their odds by producing enormous amounts of pollen. Ten million grains from one cluster of birch catkins, for example. That’s billions of pollen grains from a single tree.

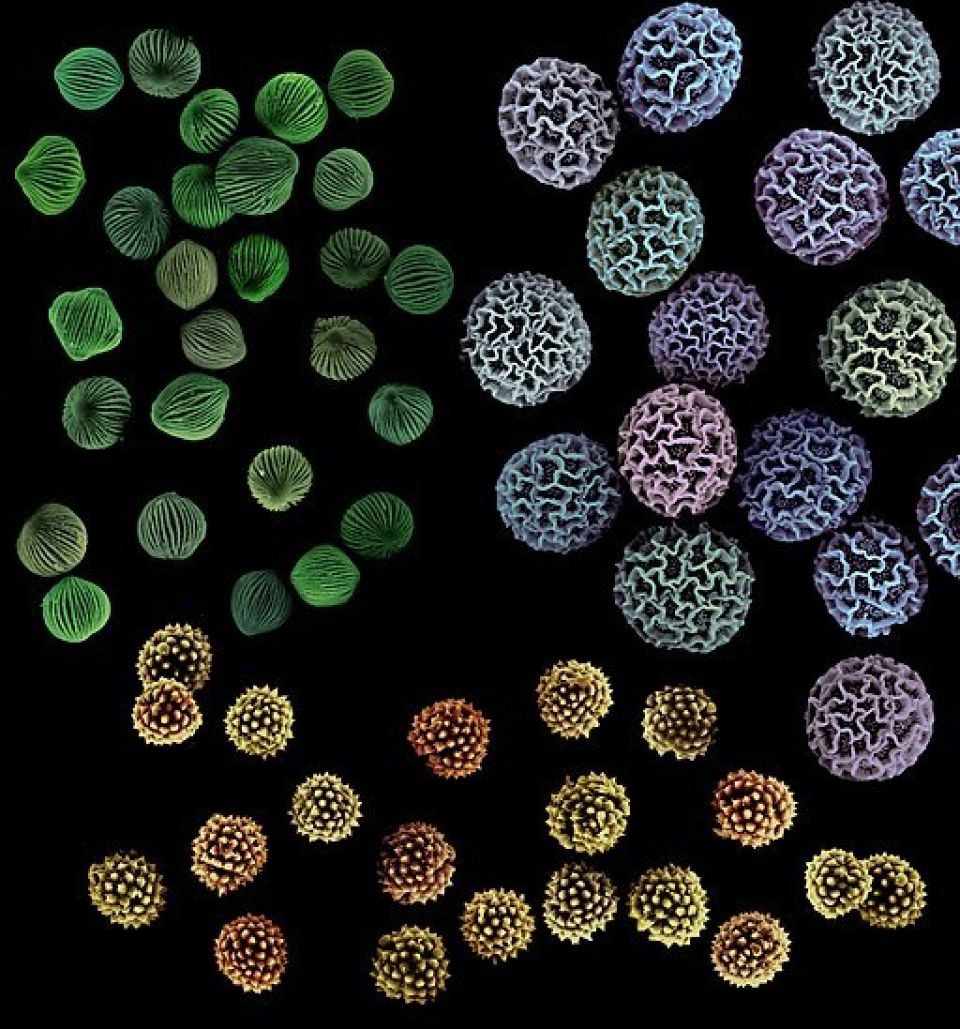

Airborne pollen itself is pretty incredible, the grains are lightweight, designed to float, not stick. Some pollen even has air sacs that boosts its buoyancy. And when seen under the microscope they come in all sorts of beautiful shapes and textures. In fact pollen identification is used in many other fields of science such as archaeology and forensics. Basically pollen gets everywhere and each geographical area and period of time in history has particular types of pollen associated with it which acts like a fingerprint. This information is used to date and identify locations of objects and animals including human remains.

These days pollen is shed most of the year. Something hay fever sufferers will be very aware of, depending on the type of pollen they’re allergic too. Did you know that it is generally the wind-borne pollen grains that cause seasonal allergies? The sticky larger pollen grains carried by bees and butterflies doesn’t get into the air as much for us to breathe in. Trees produce clouds of wind-borne pollen in spring. By summer, grasses take over and start using the wind to pollinate (including cereal crops like wheat and corn), they are joined by wildflowers and field weeds, this continues on into the autumn. Grasses are the most important producers of allergy inducing pollen in most temperate regions, with lowland or meadow species producing more pollen than upland or moorland species.

Best times to go on catkin watch

Here are some of our native common trees and when their catkins come out:

- Hazel: January to March

- Alder: February to March

- Silver birch: March to May

- Oak: April to May

- White willow: April to May.

What’s in a flower? What we tend to think of as a typical flower is only the more showy and scented form where pollen transport is provided by other creatures. Wind-pollinated flowers are usually overlooked and typically have the following characteristics:

- No bright colours, special odours, or nectar

- Small

- Most have no petals

- Stamens and stigmas exposed to air currents

- Large amount of pollen

- Pollen smooth, light, easily airborne

- Pollen grains that depend on the wind are tiny compared to those that are moved by animals.

- Stigma feathery to catch pollen from wind

Wind pollination as a strategy is effective in woods with many individuals of the same species growing near each other, in other circumstances it has its shortcomings, particularly in mixed-species stands and in fragmented landscapes. Although some pollen can travel great distances, it doesn’t remain viable for very long, and most airborne pollen comes to rest close to the tree that produced it. So, it is not as effective at delivering pollen to distant trees. It is very expensive, energetically, for the parent tree to produce such large quantities, and seems wasteful when so much pollen never reaches its intended target.

It may seem that trees and plants that use insects and animals for pollination are better off as they have to produce much less pollen and their helpers can transport that pollen much further and directly to the right place. There is still a cost, those trees have to produce flashier scented flowers and nutritious nectar to attract and pay for their staff to do the deed. So either strategies can be a useful option depending on the conditions around the tree. Indeed some special trees are capable of both.

Still it does sound like wind pollination is less complex than animal pollination and not as effective. It may surprise you then that there are at least 65 species of wind-pollinated plants that evolved from insect-pollinated species. Researchers hypothesize that these changes in the past occurred in response to unreliability or scarcity of animal pollinators. As insect populations are plummeting globally due to climate change, pesticides and habitat loss, will more plants that now rely on insect pollinators evolve to rely on the wind? Only time will tell, in the meantime we can all look out for the zingy fresh green of lambs’ tails and other catkins along with the smaller hidden flowers sprouting on our trees across the country. A sure clarion call that Spring and its delights is just around the corner. We’d love you to send us your signs of spring pictures.

By Gurnam Bubber

Donate to Trees for Cities and together we can help cities grow into greener, cleaner and healthier places for people to live and work worldwide.

Donate